Introduction

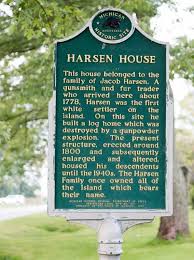

Brenda L. Williams’ blog TappingRoots (Dec. 30, 2019) presented “Lost in Translation: Frances Harsen, an Indian Woman” as a narrative of injustice and gendered exclusion. The post describes Frances, wife of Jacob Harsen II, as a Native woman marginalized by both the probate court and her husband’s relatives after his death in 1843. While Williams’ account draws on legitimate probate and guardianship records from St. Clair County, Michigan, it weaves those facts into a moralized story about greed, erasure, and the silencing of Indigenous women.

Her article raises valid social themes but blends interpretation, conjecture, and documented fact in ways that warrant clarification.

Verified Record: Frances (“Fanny”) Harsen in Probate Context

The St. Clair County Probate Book A (1843) confirms that Jacob Harsen II died intestate and that his widow was identified as “Frances Harsen, an Indian woman.” This wording appears in the official guardianship file, a point correctly cited by Williams. She accurately notes that Frances could not speak English and required a representative in court.

However, the available records show procedural exclusion, not moral persecution. At that time, Michigan’s new state laws recognized only civil or church-registered marriages, and many long-standing “country marriages” lost legal standing. Frances’ limited authority in probate proceedings reflected legal formality, not necessarily personal animus.

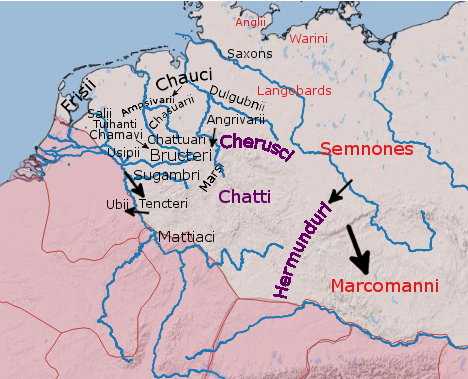

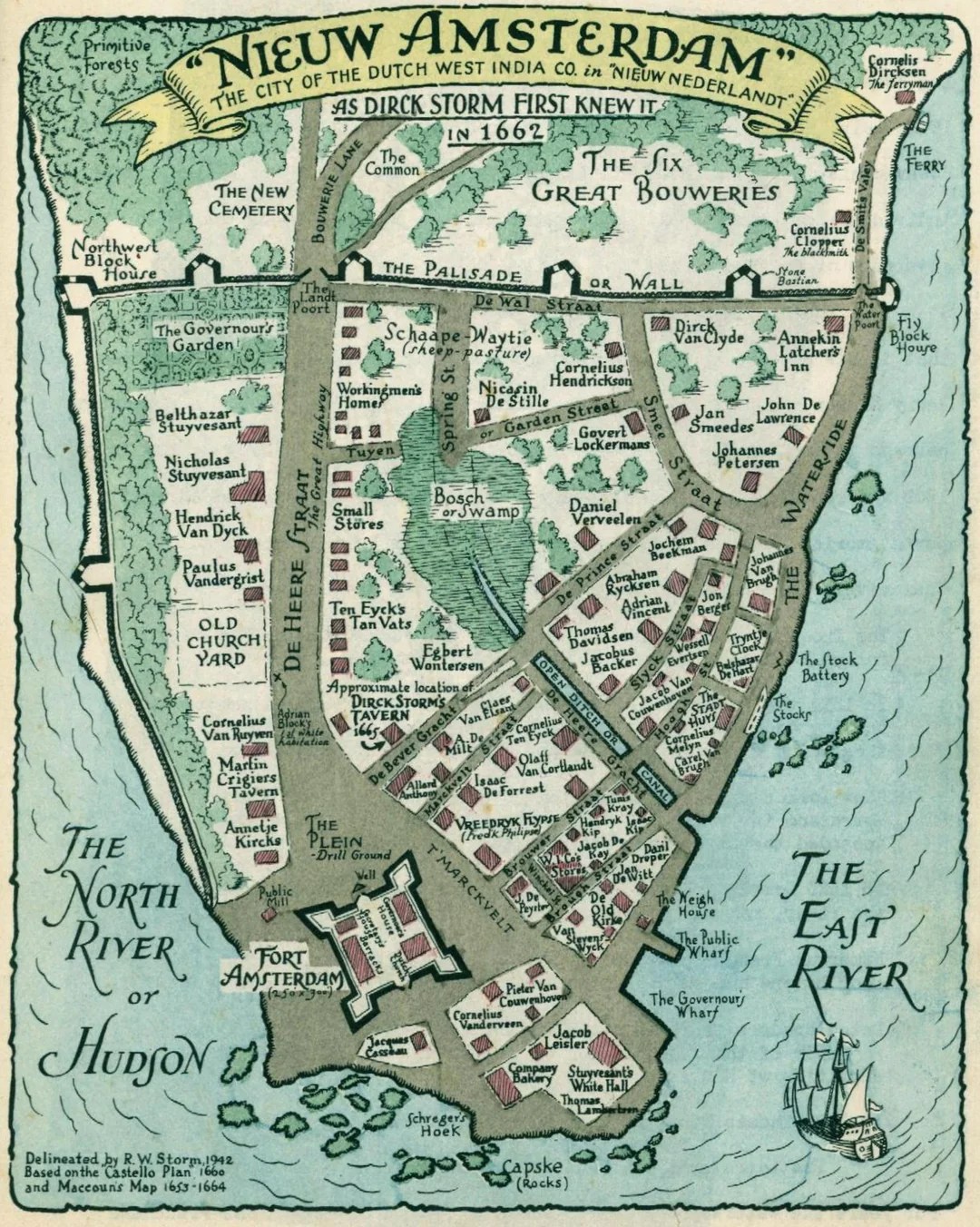

Frontier Marriage and Legal Realities

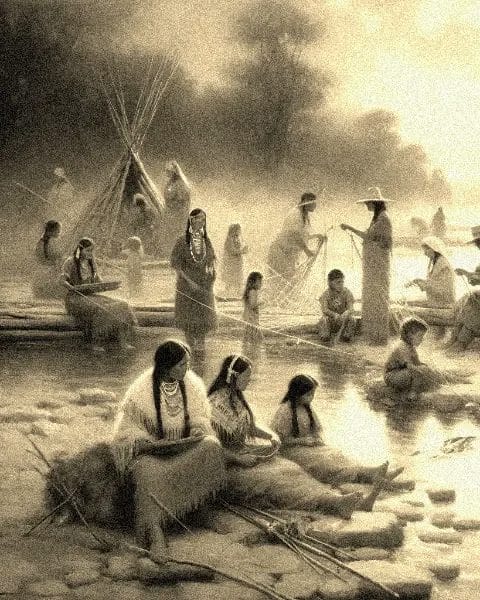

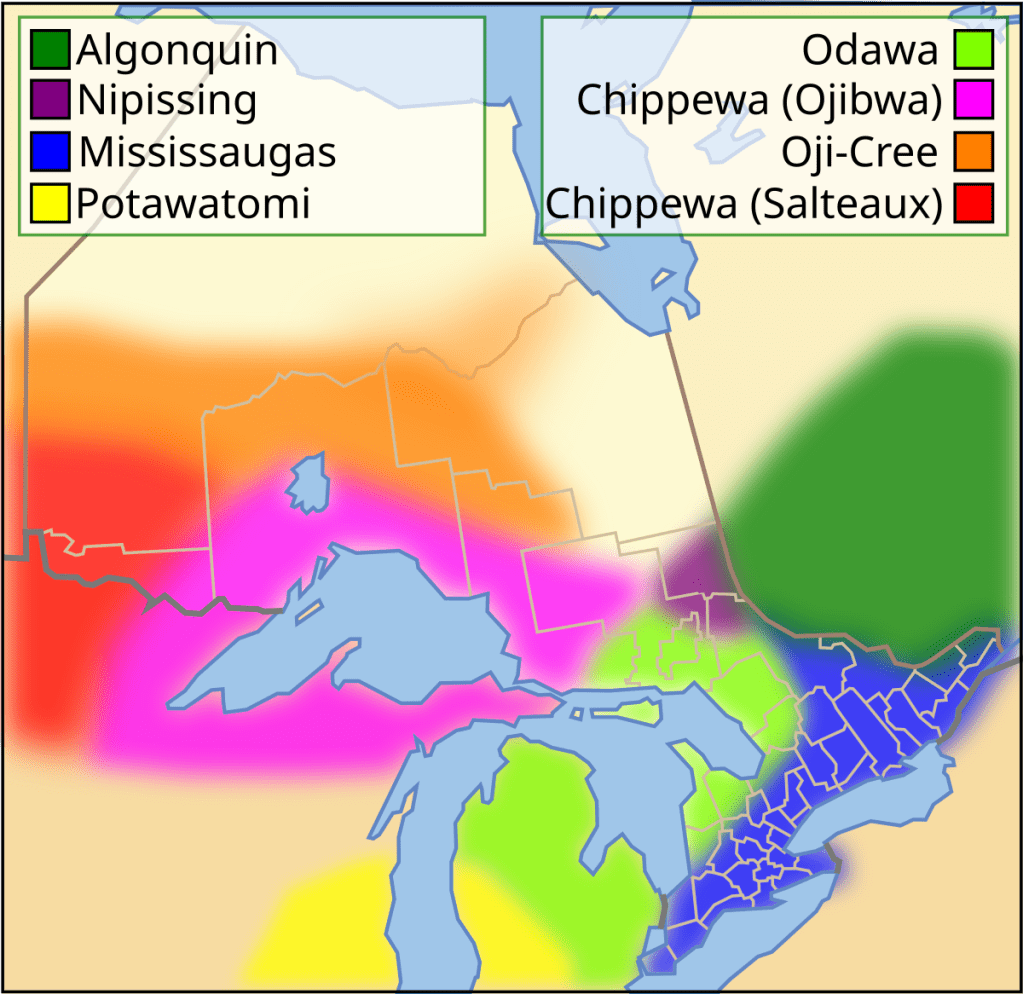

Across the Great Lakes, unions “à la façon du pays” (in the custom of the country) between traders and Indigenous women were common before statehood. When American jurisdiction replaced earlier French and British systems, these partnerships often became legally invisible. Frances’ case fits this transitional pattern.

Her inability to act fully as administrator stemmed from statute, not a deliberate act of suppression by the Harsen family or court.

Continuity, Not Erasure: Mary Polly Lawton (Laughton)

Multiple records in St. Clair County and nearby Ontario show Mary Polly Lawton (Laughton) living in the same extended community of mixed European and Native descent along the St. Clair River. She represents a later generation of the Harsen–Jacobs kin group, and several genealogical compilations connect her line to the Harsens through maternal ancestry.

Williams’ article mentions Mary as a ward of William Harsen Jr. in 1848 but stops there. Independent evidence indicates that Mary retained property and kinship ties within the Harsen–Laughton network, suggesting cultural continuity rather than disappearance. That context extends beyond Williams’ analysis but supports a fuller understanding of Native persistence in the delta region.

Walpole Island and the Question of Unceded Land

While Lost in Translation focuses narrowly on the family probate, it references material from a Heritage Canadiana reel (C-9638) dealing with Indian Affairs. Broader historical research shows that Walpole Island First Nation (Bkejwanong)—just across the channel from Harsen’s Island—has long regarded the area as unceded territory.

Petitions from the 1840s onward sought recognition of their continued occupation, and modern legal reviews by the Chiefs of Ontario still note the ambiguous treaty status of Harsen’s Island. Though Williams did not elaborate on this, placing Frances and her descendants within that unceded landscape gives their story crucial political and cultural context.

Interpreting the Evidence Responsibly

Williams’ portrayal of Fanny Harsen as “lost in translation” emphasizes gender, race, and morality, but her conclusions exceed what the cited documents show. The probate and guardianship files confirm Frances’ ethnicity and limited legal agency, yet they contain no findings of deliberate fraud or organized suppression by relatives.

Her narrative phrase that “white men closed ranks” and that Fanny was “victimized” reflects interpretive framing rather than textual quotation. Responsible genealogical writing distinguishes between evidence and inference—something that can be clarified without dismissing her broader moral concerns.

Evaluating the “Poor Character” Claim about William Harsen Jr.

In the same blog post, Williams writes:

“Sadly, evidence of William Harsen Jr.’s poor character and untrustworthiness was revealed time and time again in the estate records.”

She then describes a $74.05 payment from the Department of Indian Affairs in 1846 that she says was not recorded in the estate accounts, concluding, “He and Mr. Smith must have just pocketed the money.”

Those statements are Williams’ interpretations; no citation, image, or docket reference is provided alongside the moral judgment. The St. Clair probate and guardianship documents on Ancestry (which she lists in her references) record transactions but contain no explicit language about moral character, fraud, or untrustworthiness.

Without contemporaneous testimony or a judicial finding, that description must be treated as narrative inference, not evidence.

When secondary authors apply ethical labels to historical figures, historians must ask whether the judgment stems from the documents themselves or from modern moral interpretation.

Historical Writing in the 2010s: Cultural Lenses and Presentism

Historical and genealogical blogs written during the late 2010s often reflected a cultural atmosphere that emphasized social justice, gender equality, and decolonization. This approach added needed visibility for marginalized voices but sometimes encouraged presentism—evaluating nineteenth-century actors through modern moral standards.

Lost in Translation belongs to that moment. Its themes of race and patriarchy mirror 2010s discourse more than mid-nineteenth-century legal context. Recognizing that lens helps readers separate cultural commentary from archival fact.

In short, when analyzing any historical narrative, one must consider the moment and person that produced it as well as the evidence it cites.

Analysis of Brenda Williams’ References

Williams’ bibliography lists over 40 items, ranging from court files to tertiary web pages. The issue is not the existence of her sources, but how they are used. Below is a concise analysis of each citation group, showing which support her claims and which do not.

| Source | Type | What It Actually Shows | Relation to Her Claims |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Clair Probate & Guardianships (Ancestry, 2019) | Primary | Lists Frances Harsen as “an Indian woman,” and records guardianships for Jacob and Mary Laughton. | Supports factual context but does not state that Frances was defrauded or that William Jr. was dishonest. |

| Indian Affairs Reel C-9638 (Heritage Canadiana) | Primary | Contains 1840s ledgers referencing payments to traders (possibly David Laughton, Jacob Harsen). | Neutral; no entry proving money was pocketed. |

| U.S. Federal Censuses (1830–1860) | Primary | Show residency and household composition in Clay Township. | Neutral; census data provide demographics, not moral or racial descriptors. |

| Algonac-Clay Historical Society / Collins, “Old Johnson House” | Secondary | Local settler history. | Contextual only; no mention of Frances or Mary. |

| Detmeter, “Jacob Harsen and the Early Settlement of Harsen’s Island” | Secondary | Early settler overview. | Contextual; doesn’t support claims of misconduct or erasure. |

| Burton, City of Detroit (1922) | Secondary | Biographical note on David Cooper (probate administrator). | Neutral; no support for any moral claims. |

| Peterson (1981), Berger (1997), Tavers (2015), McDonnell (2015), Tanner (1987) | Scholarly secondary | Legitimate academic studies of mixed marriages, policy, and treaties. | Background only; no connection to individual Harsen cases. |

| Blackbird (1887; 1900) | Primary / memoir | Indigenous-author history of Ottawa and Chippewa peoples. | General Indigenous viewpoint; not specific evidence for Frances or Mary. |

| Find-a-Grave pages (Jacob Peter Harsen; Nancy Brakeman) | Tertiary | Grave data compiled by users. | Not probative. Used illustratively. |

| Genealogy.com, WikiTree, Bob’s Genealogy Filing Cabinet | Tertiary | User-contributed genealogical information. | Unreliable as evidence. Cannot substantiate legal or moral claims. |

| Women’s Rights sources (Donnaway 2018; Susan B. Anthony House; Women’s International Center) | Secondary | Context for women’s legal status in the 1800s. | General context, not case-specific. |

| NPS, EarlyChicago.com, Chicago Portage Ledger articles, Kozlow (AFC Records) | Secondary | Fur-trade history. | Relevant background but unrelated to Frances or William Jr. |

| House Document on Potawatomi land grants (U.S. Congress) | Primary | Mentions David Laughton married to a Potawatomi woman and references “her child.” | Partially supportive of mixed-heritage lineage but does not name Mary specifically. |

| Lytwyn (2008), Walpole Island TEK Study | Secondary | Indigenous land-use studies. | Contextual; does not reference Harsens. |

| Port Huron Times (1912); Delta News (1965) | Secondary | Obituary and tombstone notes. | Neutral. Neither discusses Frances or William Jr.’s conduct. |

| Michigan Historical Society (1912) | Secondary | “Old Baldoon” settlement notes. | Unrelated. |

Overall Pattern:

Only a handful of Williams’ references are genuine primary records about Frances or her immediate family; the rest are interpretive or contextual. None provide documentary proof of William Harsen Jr.’s “poor character” or of Mary Laughton being both David’s daughter and Indigenous. The bibliography’s breadth lends an appearance of depth, but most citations do not substantiate the moral conclusions drawn from them.

Conclusion

The verified probate record shows Frances Harsen acknowledged as Jacob Harsen II’s widow and described as an “Indian woman,” but not erased from the proceedings.

William Harsen Jr. did serve as guardian for Jacob P. Harsen and later for Mary Laughton, but the available files contain no adjudicated misconduct.

The accusation of “poor character” in Williams’ article is interpretive, not evidentiary.

Frances, Mary, and their descendants lived within a mixed community on territory the Walpole Island First Nation still considers its own—an enduring testimony to Indigenous continuity in the Great Lakes borderlands.

Separating evidence from interpretation does not diminish their story; it grounds it more firmly in the historical record.

References

- St. Clair County (Michigan) Probate Court, Book A (1843): Estate of Jacob Harsen II.

- “Guardianship of Frances Harsen, An Indian Woman,” St. Clair County Probate Records, via Ancestry (Referenced in TappingRoots post).

- Brenda L. Williams, “Lost in Translation: Frances Harsen, an Indian Woman,” TappingRoots, Dec 30 2019.

- Heritage Canadiana Reel C-9638, Indian Affairs Western Superintendency Records (cited by Williams).

- Revised Statutes of Michigan (1846), “Of Marriage and Divorce.”

- Jennifer S. H. Brown, Strangers in Blood: Fur-Trade Company Families in Indian Country (UBC Press, 1980).

- Chiefs of Ontario, Historical Report Assessing Métis and Indigenous Claims to Rights in S.O.N. Territory, April 2025.

- Heritage Matters, “Bkejwanong: Sustaining a 6,000-Year-Old Conservation Legacy,” 2023.

Disclaimer

This article is based on public and archival records, verified secondary sources, and independent analysis. Every effort has been made to represent the documentary record accurately. Interpretations concerning historical figures reflect analysis of available evidence and are not intended as personal statements about any living individuals. Readers are encouraged to consult the cited primary materials and form their own conclusions.